Volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambivalence, or VUCA for short – is the world for which agile frameworks and methods are created. During the COVID-19 crisis, we are all experiencing VUCA. In these situations, working in an agile organization can have its advantages. Agile – in the literal sense – organizations can adapt quickly to new framework conditions. They integrate their employees’ creative potential in order to react to changing markets and align their portfolio in the short term. Employees are appreciated and find meaning in their daily work. Therefore, agile organizations should be well equipped to deal with crisis situations.

Over the past few years, many organizations have begun to adopt agile frameworks. Mostly, these initiatives start in IT and then radiate to other areas of the company. Surveys show that while agile working is beneficial, the goal of an agile organization is rarely achieved. Although 89 percent of respondents see an improvement compared to efforts when adopting agile approaches [1], only 6 percent of respondents to another survey [2] say agile practices increase adaptability to changing market conditions.

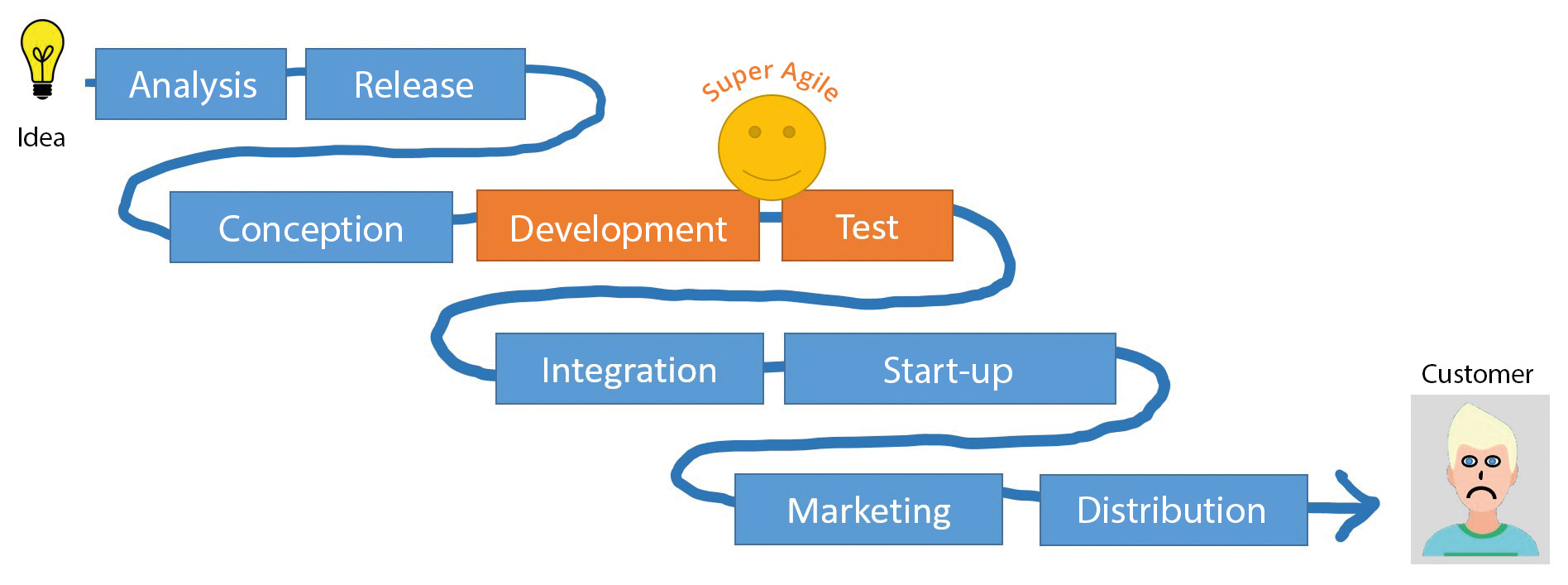

This is easy to understand when you consider that the value chains of larger organizations do not run within one team, but often involve multiple teams or departments. What good is a super-agile development team if areas upstream or downstream of development are not equally agile? Then it’s hardly possible to bring new initiatives or product ideas to the customer in a short time. The agile team remains an island and the goal of the agile organization (business agility) is not achieved (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Value stream

What is culture?

Some people would define company culture as “the way we work,” or “our company climate,” or “the rituals we set”. The organizational psychologist Edgar Schein expresses it differently: “Culture is the sum of all common and self-evident assumptions that a group has learned in the course of its history”. [3] Culture significantly influences how people behave and interact. While processes define rules and an explicit formal framework within which people should operate within an organization, culture represents an implicitly learned framework. It is not formally specified, is unconscious, and therefore, more difficult to capture.

STAY TUNED

Learn more about DevOpsCon

So, in order to develop culture, it is necessary to have new learning experiences. Learning seems easy because most of us have done it a lot. Moreover, in IT we are used to learning. Unfortunately, the complicating factor is that we have to unlearn what we previously learned if it is not compatible with a new (perhaps agile) culture. It is necessary that we clear out our bag to make room for the new. Culture is valuable because it provides stability and predictability. Stable culture provides a framework where members of an organization can move safely.

Culture development as the key

Becoming more agile as an organization requires the development of agile culture in many areas along the value chain. Most agile frameworks and movements include values as a prerequisite for a successful application:

- In Scrum, it’s respect, courage, openness, focus, and commitment.

- In Kanban, it’s respect, transparency, balance, collaboration, customer focus, workflow, leadership, understanding, and agreement.

- In DevOps, it’s trust, empathy, collaboration, and transparency.

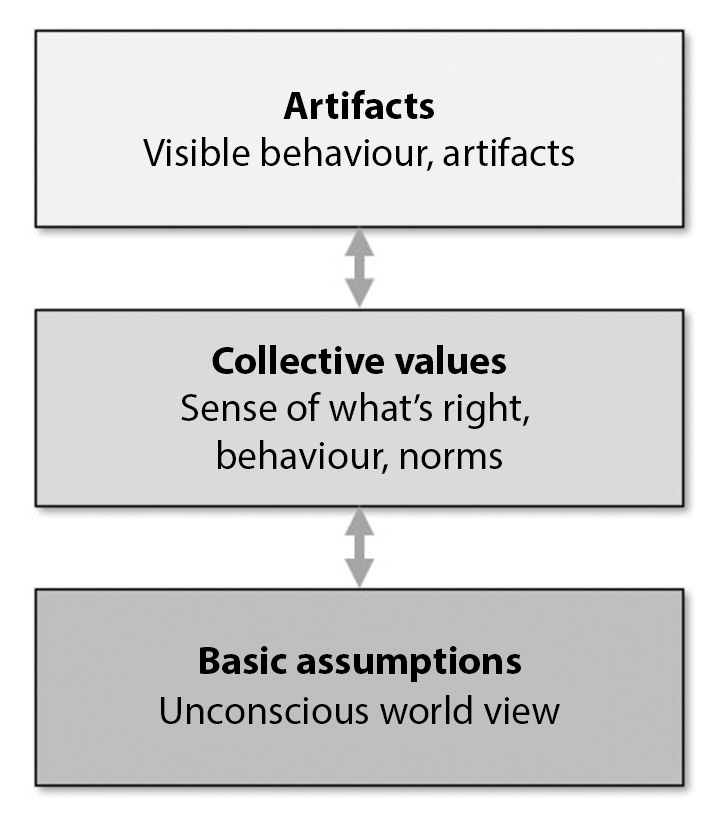

As you can see, there is a lot of overlap in this set of values. Values are closely related to culture. Edgar Schein makes this visible in his culture level model (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Culture level model

Agile practices at level 1 such as task boards, reviews, or stand-ups are found at the artifact level. Beyond the use of these practices, becoming agile as an organization requires active culture development at level 2 of the collective values. Influencing this level is infinitely more difficult. The basic assumptions about the world at level 3 can hardly be changed. Here, it is advisable that you ensure that employees share a compatible worldview when they are hired.

Where do we stand?

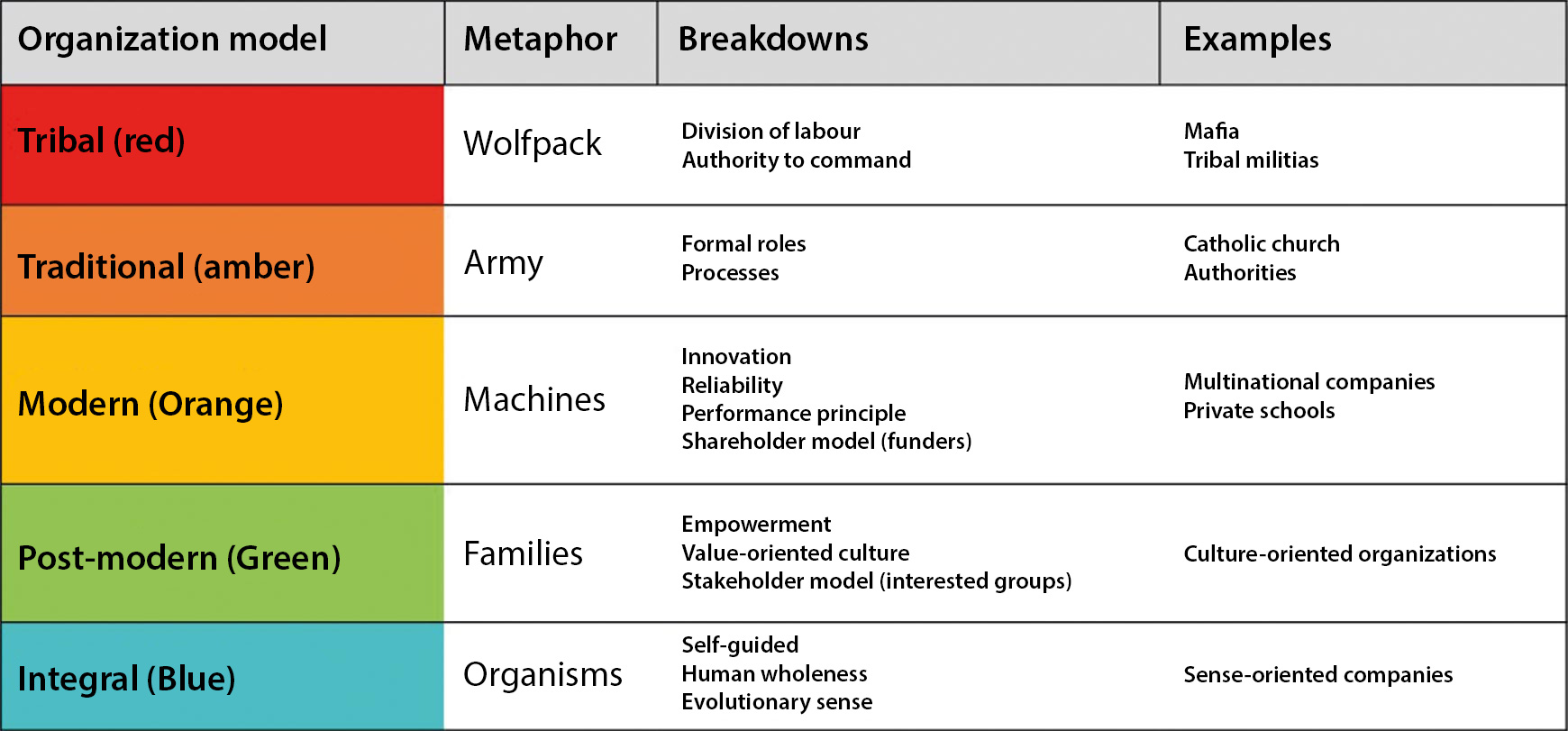

Frédéric Laloux [4] proposes a gradation of organizational models (Fig. 3). Each level is associated with a color. Most companies in Germany probably belong to the modern model, some to the postmodern model, and only a few to the integral model. Agile approaches are more likely to be classified as postmodern and integral models. The classification is not clear-cut, as different models can be found within an organization under certain circumstances. For example, this is the case when individual organizational areas move in the direction of agile approaches and the integral model, while others organize themselves according to classical approaches. In this respect, the levels do not represent a valuation, since different models may be more appropriate depending on the problem. Instead of “Agile Organization”, we can also use the term “Integral Organization”, as it emphasizes culture more than techniques.

Fig. 3: Organizational models

Fig. 3: Organizational models

How is culture created?

Even big companies were once smaller at some point. Perhaps there was a breakthrough innovation or a new product that excited many customers. Certain actions are experienced successfully, but others are not. That’s how people learn what works and internalize it over time. Foundation myths and success stories emerge. In a time of stable structures, high specialization can bring success because it allows us to keep improving the efficiency of a system’s parts. If we have good experiences with this, we will internalize these actions over time and may no longer question them. They become part of our self-image and culture. In this respect, culture is an expression of previously successful actions. If these actions are of a general nature, they find expression in teaching and are anchored at an early stage.

But, if external circumstances change, it might become necessary to learn new, different ways of acting in order to be successful. Since humans (fortunately) are not computers, we cannot program them into ourselves. Regulations and processes also act as an attempt to remotely control human actions, which many people reject. In order to change culture, we need the space to have new experiences and find out which actions are successful under new conditions. This is how new success stories emerge and how culture can change. That is why the experiment is perhaps the most important tool in the agile toolbox. An experiment can be staffing a team with people who are open to learning other things in addition to their current knowledge (T-Shape) instead of specialists. If it turns out that this kind of team is better at delivering results in a volatile and complex environment, it can change the culture.

Can we measure culture?

It probably isn’t possible to measure culture technically, but we can observe and classify it. As we can see in the culture level model (Fig. 2), culture expresses itself through behavior as an expression of valid norms. We can observe behavior. How are mistakes reacted to? Is the first reaction to look for someone to blame or are mistakes openly named and seen as an opportunity for learning and improvement? Do team members go home on the dot, or do they complete their work, even if it takes longer? Do sarcasm and resignation dominate the discussion or is there lively and constructive conversation? Are decisions made within specific groups or on an issue-by-issue basis involving all participants? Is research done at work or is learning a private matter? Do leaders stand for management and control or do they act as role models? Who gets promoted and why? What status symbols are there?

Beliefs also reveal a lot about the prevailing culture. Conversations with people in an organization can help identify them. A few examples:

- “Many accomplish more than a few.”

- “If you start early, you finish early.”

- “Experts are best at solving problems.”

- “Redundancy is bad.”

- “Products must be error-free.”

- “No decision is made without numbers.”

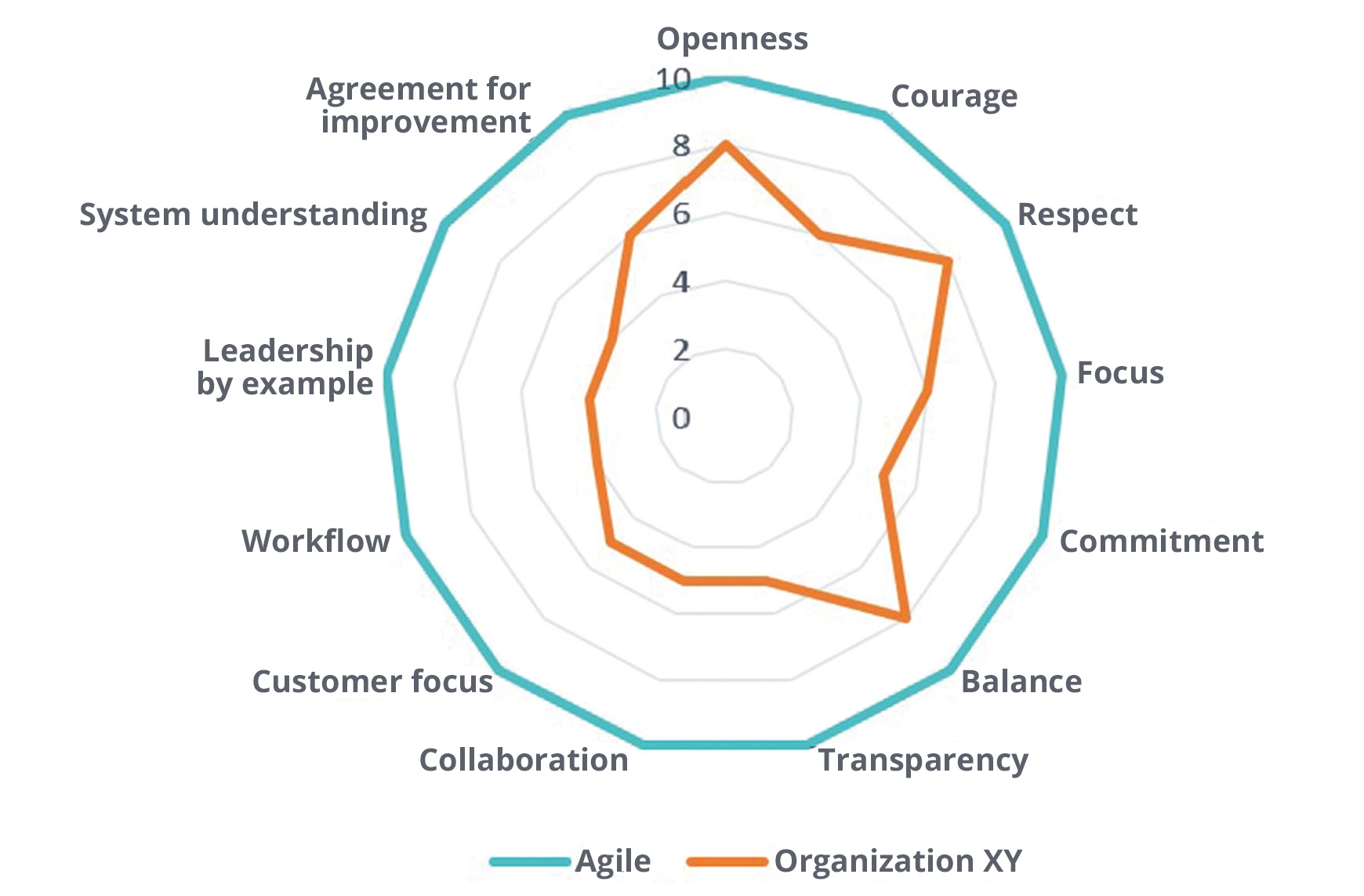

Culture can be made visible by formulating valid beliefs. It is not uncommon for companies to formulate values and publish them in a central location, for example in a company wiki or on posters. However, this does not mean that these formulated values are also the lived values. In most cases, they describe wishful thinking or a goal. They are only of limited use as a source of culture assessment. We can assign our observations to values and gain an overview of the actual culture (Fig. 4). This is a good basis for further culture development.

Fig. 4: Cultural assessment

Fig. 4: Cultural assessment

Cultural impact

And what impact does organizational culture have on daily work? Let’s use an example of the fictitious company Orange GmbH, which operates primarily from the modern paradigm. The initiative for a new product comes from the management circle. The management group decides to manufacture the new product. The teams have no expertise in manufacturing the product, so the first thing step is to organize central training and select a team to implement it. The team is already well-utilized and is skeptical about the new initiative. First, a comprehensive analysis is carried out by another department to know exactly what the product should look like before implementation can begin. The product is manufactured, with repeated disagreements over the interpretation of requirements. After a lot of overtime, the product goes into operation and is taken over by the operations team. Sometime later, there is a critical error in production. After some commotion, a former colleague who is no longer part of the team is identified as the culprit. Management reacts with stricter rules for release approval. The team is unsettled and no longer dares to innovate. Sarcasm characterizes the discussion. Service is done by the book and teams are suspicious of new initiatives. The product becomes worse and worse because it no longer meets customer requirements.

Things might have been different at the equally fictitious Petrol GmbH, which operates primarily from the integrative paradigm. The development team works close to the customer and has an idea for a new initiative. Since other teams are also affected by this, consultations take place between teams. Objections lead to the initiative being adjusted. Once there are no more serious objections, the initiative is launched. The product is produced with a high level of motivation, primarily by the team that contributed the initiative, with other teams contributing in a timely manner, providing capacities for this purpose. All relevant tasks, including analysis and design, are performed by the cross-functional team. The team acquires any missing expertise during implementation and organizes its own training courses. The team also plans its own tasks so that they can be performed without any significant overtime. It assumes operational responsibility and regularly delivers improvements. Later, when a critical production error occurs, the team analyzes the problem and optimizes internal quality assurance to avoid such errors in the future. Identification with the product is very high and customers are very satisfied. The team has more ideas for new initiatives and discusses them lively with colleagues from other teams. The work is enjoyable and seen as meaningful.

Are these extreme examples? Perhaps. But they show how differently product development can proceed in different cultural contexts.

Conclusion

Especially in the context of agile organizational development, the topic of culture plays a central role. It is not for nothing that values are a component of many agile frameworks. At its core, it is about developing learned attitudes and mindsets of people in order to create opportunities for agile organizations. This goes far beyond the use of artifacts such as boards or stand-ups and may require a lot of time and energy. However, this effort is worthwhile if it creates an organization that can respond flexibly to change while being attractive to people.

In the first part of this series, we looked at what culture is, how culture can be understood, and the impact it has on the way we work in an organization. Now, you might be curious to see how cultural change can be achieved. This is the topic of the second part, which deals with concrete approaches to culture development and their implementation.

Links & Literature

[1] Hochschule Koblenz: „Status Quo (Scaled) Agile 2020“: www.status-quo-agile.de

[2] „13th Annual State of Agile Report“: www.stateofagile.com

[3] Schein, Edgar H.: „The Corporate Culture Survival Guide“; Wiley & Sons, 2009

[4] Laloux, Frédéric: „Reinventing Organizations. Ein Leitfaden zur Gestaltung sinnstiftender Formen der Zusammenarbeit“; Vahlen Verlag, 2016

6 months access to session recordings.

6 months access to session recordings.